“I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies,” writes the late, great, Douglas Adams in The Salmon of Doubt:

“1. Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

I teach in the post-compulsory education sector in the UK, which comprises further education colleges, sixth form colleges, specialist colleges such as Leeds College of Building (LCB), and private training organisations. At LCB we provide high quality, specialist construction and building services engineering vocational education.

I teach electrical apprentices who attend as day-release students. My students age range is typically between the ages of 16 and 21. They usually the start on level three apprenticeship either straight from school or having done one year in college on a full-time level two electrical course whilst obtaining maths and English GCSEs which is an entry requirement to the apprenticeship program. However, I often have students in their 20s and 30s, and have even had a student in his 50s.

In this blog I’m going to discuss digital literacy – what has been written about it by other people, and how my apprentices use technology. I’m going to write about my own digital journey, and contrast it with that of my apprentices. I’ll consider what this means for my pedagogical approaches, and the importance of digital literacy for this group of learners.

Before I get into all that though, it is important to understand the world in which I teach. In future, electrical installations will consist of distributed local power generation. Devices, such as heaters, machinery, car charging and the like, will communicate with smart meters and use power, or in the case of batteries, charge when the price is very low, or free or the consumer will even be paid to take energy off the grid. This new landscape of 21st-century electrical installation will be smart and will require devices to be programmed. This will therefore require high levels of digital literacy in electricians to install the systems.

Previous iterations of the electrical apprenticeship (until 2018) included mandatory level two functional skills training in ICT, giving apprentices key digital skills enabling them to use these when constructing their online portfolios or just in the efficient use of Word, Google Chrome, or OneDrive (City & Guilds, 2018). Without this module, they would not have been allowed to progress to their endpoint assessment and fully qualify as electricians in England. Since 2018, however, this requirement has been removed from the apprenticeship standard. This is unfortunate as in the same period there has been the rapid adoption of smart technologies in the electrical industry. It is therefore essential that digital skills are included in electrical education.

Douglas Adams was hugely enthusiastic about technology, and his ‘Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy’ inspired early work on the internet. The quote I started with anticipates the thoughts of Marc Prensky (2001) in his influential work on Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants. Adams succinctly and humorously describes the situation in which many of us find ourselves – that is that if we’ve grown up with technology, we can cope, understand, and use it. However, after a certain age, we struggle to understand and use it.

Echoing Douglas Adams, Prensky suggests people can be classified as Digital Natives or Digital Immigrants based on their year of birth. After 1980 they are natives – people who have grown up with the technology in a media-rich world and instinctively know how to use it. Before 1980 they are immigrants – people who haven’t grown up with technology, were born before mass digital technology, have had the technology thrust on them and find it harder to accept and use new technology.

Prensky suggests that the native would be fluent in the digital languages of computers, video games and the internet. They should be better multitaskers, prefer digital communication – and as they have grown up with a digital world – the use of digital tools should be second nature to them. They should also prefer experiential learning rather than traditional passive learning. The immigrant, however, will use digital technology, but will not find it second nature. Digital immigrants must put in extra effort to use digital tools and they have a cautious approach to technology. They are less digitally intuitive. Traditional communication is preferred over digital, as are traditional forms of learning.

Children are naturally curious, (Piaget, 1964) and this can help them to learn to navigate digital tools. This natural curiosity, combined with ready access to digital tools through childhood could help children to develop as digital natives. Sugata Mitra conducted the famous Hole in the Wall study (2001) in which he placed a computer in the wall of a slum in Delhi. In this experiment he made the computer accessible only to children by the physical design of the access to the keyboard and monitor position. Mitra claims this experiment as a massive success, demonstrating what he calls Minimally Invasive Education where the children taught themselves. Others, however, have suggested he has exaggerated its success. As Warschauer, (2003) pointed out due to the lack of scaffolded learning this minimally invasive education only produced surface or shallow learning. In addition, it was noted that often the internet DSL link did not work, the equipment failed, and eventually the site was abandoned.

Most of my electrical apprentices should be Natives as they have grown up with technology and they should have the appropriate level of digital literacy to enable them to navigate through their apprenticeship. Why is the digital literacy of apprentices important? The possibilities that digital spaces also give the opportunity of creating virtual spaces of community and belonging. Vocational education happens both in the classroom and in the workplace. Students on vocational programs often only meet one day a week in person, however, by utilising the power of the classroom in their pocket an extension of the learning environment can be created. By moving all content and as much assessment as possible into the digital domain, a virtual college is available to them 24/7. Not only for accessing their theoretical work, or even the ability to easily gather evidence for their work portfolios, but also creating spaces where they can share information with others in their group. They can form active online communities between the lessons each week, removing the sense that they are only part of the group for one day a week. Checking up on each other, arranging social activities or just to check which room they will be in on any given week.

Sense of belonging is Important as it fosters better student wellbeing, together with better educational attainment (Korpershoek et al., 2020). The sense of relational belonging can be enhanced using digital tools which is especially important with day release students. Gravett et al. (2022) discusses this from the perspective of higher education students, but it can also be considered in the context of further education apprentices. Gravett et al. (2022) argue that the students of today experience their learning spaces very differently than did students in the past and that the use of digital spaces is now taken as an accepted and expected part of the student experience. Therefore, the fostering of belonging through our digital tools and spaces should be encouraged. Digital education offers the possibility of transformational change, connectedness, and unlimited access to learning materials (Haleem et al., 2022). To maximise these benefits, we need a better understanding of the relationship our students have with digital technology and how it differs from our own.

Throughout my life, I have been fascinated by technology. I recall spending time in the last year of primary school begging to be allowed to play with the school’s Research Machines 480z and trying to modify BASIC programs so that they would work on that machine. In secondary school, I joined the computer club and had exposure to Spectrums, Commodore 64s, and even a Sinclair QL – remember them? I was always taken with the possibilities that technology could offer, rather than just gaming like everyone around me. I was given a ZX81 for Christmas around the same time, with the wobbling RAM pack, and after spending time writing – well, rather copying – skiing games into the machine, I set about writing an information system for it. It would tell you the news, the weather, what’s on TV, etc. And I made something that was quite like teletext, and you could ask it what the weather was today – however, this being before the connection to the internet, I had to input the news and weather each day into the system.

When I first started secondary school in 1983, we had one computer in its own specialist room that you might be able to use if you were deemed able enough in maths. Through my time in secondary school, the one computer became a room of BBC Micros to finally, in the sixth form, Acorn Archimedes computers, and one Apple Macintosh 128. In the space of six years, my experience had gone from a command line to a graphic user interface, and I’m currently writing this blog on a MacBook.

This would indicate that Prensky would see me as an immigrant as I grew up during the rapid development of digital technologies rather than being “born digital” (Seely Brown, 2008). However, as someone who has grown up with computers and has used them creatively and professionally for the last 40 years, I think that the Digital Native vs. Digital Immigrant debate lacks nuance. Prensky is being incongruous as the whole modern computer industry was created by people born before 1980. Digital Native vs. Digital Immigrants does not reflect the rapid change of technology, or the relationship people have to it.

I see this digital divide through a different lens. I think that age doesn’t necessarily play a part in someone’s digital literacy. We all have different levels of experience of, and exposure to digital technology. Our skills are formed around this exposure and interaction with hardware or software. Furthermore, our motivations for using the technology will also impact our ability to engage with it (Dunn & Kennedy, 2019). In the context of observing my own students, I see this daily. If, as Prensky suggests, they should be digital natives, they should be able to navigate the digital world and have excellent digital literacy. However, they are consumers of technology. They consume YouTube, gaming sites, porn, news sites of dubious quality, and a large proportion of them consume the misinformation and misogyny of people like Andrew Tate. During their schooling, they haven’t been taught critical thinking to allow them to navigate the digital world (Polizzi, 2020). As educators it is our duty to counteract this. Indeed, our ETF professional standards for teachers within this sector state that we should “Select and use digital technologies safely and to promote learning” and “promote and support positive learner behaviour, attitudes and wellbeing.” (ETF, 2022) Thus, we should be at the forefront of giving our students the digital literacy, critical evaluation tools that they need to navigate their digital world.

This is what Paul Gilster argues in his book Digital Literacy. He states that there are a number of core competencies that must be acquired by someone so that they can successfully navigate through the internet-enabled world. He points out that being digitally literate goes beyond the ability to use a particular digital technology. Rather, he suggests that digital literacy is the ability to find and interpret information from a wide selection of digital sources and then to critically evaluate the information so that it can be used effectively. He believes that a digitally literate individual can take information from many different digital sources, synthesise it and then produce coherent information that can be communicated clearly. Digital literacy, for him, is the ability to understand information in the context of a digitally-enabled world, (Gilster, 1997)

However, the cohorts of apprentices I have encountered over the last four years do not display the level of digital literacy required as outlined by Gilster. They expect the technology to work and provide the solution, answer, or support for their work immediately and without them having to analyse the results given. They don’t seem to have the ability to use the discovery mode of learning and are afraid of exploring in case they ‘get it wrong’ or ‘break it’. I’m not sure where these responses come from; I think that maybe it’s a hangover from secondary education in the UK, which seems to have become more rigid and less based on discovery and more on exams and targets leaving less time for discovery or experimentation. They are also uncritical of the answers they are given by the technology. They will accept as fact what a quick Google search gives them. For example, every year I get the same answers on an electrical science worksheet to the question: What is a cell? Rather than giving an answer telling me about a device that produces electricity from a chemical reaction, they tell me about biological cells, membranes, and molecules as that is the first answer given by Google.

Gilster’s book was written when the world thought Apple was dead, before the return of Steve Jobs, and the iMac, iTunes, iPods, iPhones, iPads and the iCloud that dominate our world now, either in their Apple form or in the countless copies. Prensky was writing before the era of Facebook, X, TikTok and all the other social media sites that have infiltrated our world. Gilster didn’t anticipate the explosion of commercially driven internet sites where algorithms drive consumption. My learners don’t need to be explorers to engage with content, which in turn reduces their digital skills. However, Gilster’s ideas are still relevant as he states that we need to adapt our skills as the digital technologies change.

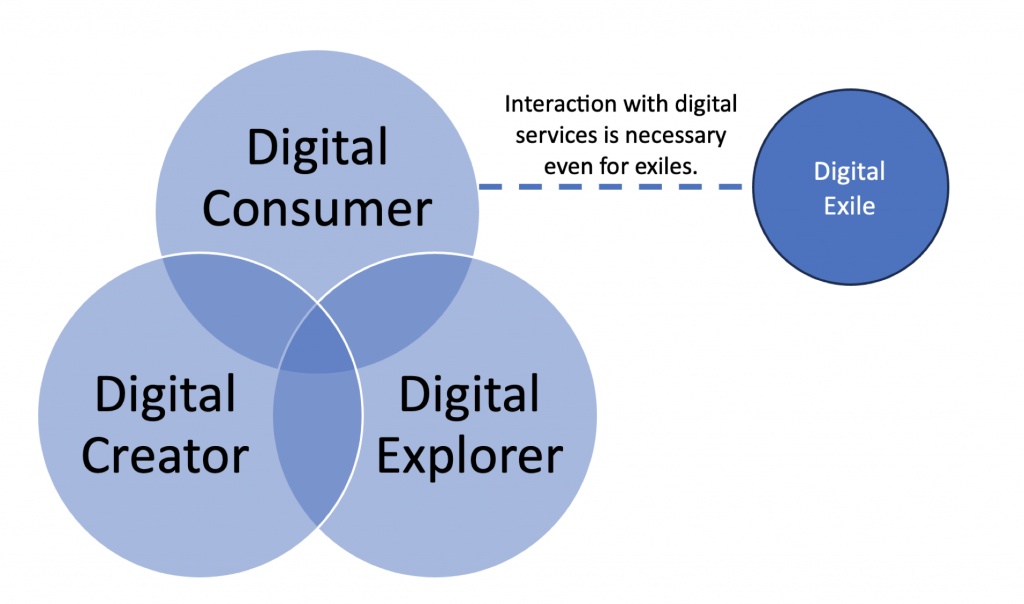

Having considered the digital landscape over the last half century, together with my own story and observing my apprentices over the last four years, I feel that Prensky’s descriptions need revising and expanding. We need a better range of descriptors to illustrate the variation in digital literacies, one that can encompass multiple identities to better understand our students, and thus develop the digital literacy of our students. Therefore, it would be better to look at the divide through the following lenses:

- A digital consumer – someone who consumes digital content.

- A digital creator – someone who creates digital content.

- A digital explorer – someone who is curious, questioning and investigates digital content.

- A digital exile – excluded from digital due to poverty, lack of access or lack of skill.

These identifiers do not have to be as rigid as in the immigrants vs. natives descriptors. One can be simultaneously a consumer and creator: for example, when creating a TikTok video, or a creator and explorer when coding new content. Equally an exile having little or no digital literacy must be a consumer at times – when accessing online services – which brings into the question of digital inequality. Unequal access to digital technology and services is something to consider in the context of other educational settings. However, my students are employed, have computing technology in their pocket (which sometimes I wish they would stop using in the classroom!) and have access to computer-enhanced classrooms when in college. This is a fortunate situation to be in and removes the worry of digital exclusion due to poverty when introducing more digital tools to the classroom. However, there could still be a level of digital exclusion due to lack of skills.

I have observed the use of digital technology by my students, and they fit into these new digital identity descriptors well. Most of them are digital consumers. They lack a lot of the necessary digital literacy as outlined by Gilster. There is a deficit in their training considering the subject they are studying and the needs of the electrical industry. They need to develop their digital skills to be creators, consumers, and explorers.

I use technology to scaffold the learning of my students. Using MS Teams to scaffold their learning in conjunction with the principles of Problem-Based Learning (PBL). PBL’s constructivist roots promote active learning with student ownership where knowledge is constructed through experience and social interaction (Barrows, 1996). Digital brings the social interaction, especially when leaners are not in college, and enables me to support their learning. This scaffolded PBL approach has been shown to reduce cognitive load, allowing for deep learning (Hmelo-Silver et al. 2007). I use MS Teams as the course repository for all the information they need for each module. Each subject or unit gets its own channel, and within that channel, I use the announcement function to break up each topic. I also use good background graphics on each header so that when the students are looking for each subject, they have a visual clue which aids in identifying the topic. I also check that it looks good and works well on phones as this is the access point my students have when not in college.

I also use Microsoft Forms to create timed multiple choice questions (MCQs) for the students which mirror the actual assessment that they will do – these can then be set as assignments in MS Teams and I can monitor the students while they are completing the tasks – it also enables me to monitor the answers and get an overall picture of which questions the cohort finds easy and which ones have been more problematic.

This data enables me to then target my teaching, using the principles of the spiral curriculum (Bruner, 1960) to bring back those subjects that need further work in future sessions. As their assessments for each module include an MCQ, this is a valid and authentic way of using digital pedagogy in formative assessments, modelling their final summative ones.

I try to make teaching spaces of psychological safety where students can ask questions, make mistakes, and ask for support, which in turn promotes deeper learning and where more demanding work can take place (Hughes et al., 2023). This approach enables my students to experiment with technology and learn to become Digital Explorers and develop their connectivism where they interact with distributed sources of information and make learning networks (Siemens, 2005).

The new landscape of digital technology within education, which is being encouraged by government in policy and funding – at LCB we have just received part of a £6.9 million funding package from government for the development of digital teaching – presents several challenges such as how to integrate the technology into the existing curriculum However, we must remember that good digital pedagogy is good pedagogy (Stommel, 2018), and we shouldn’t accept the technology just because it is new. We should critically evaluate the pedagogical usefulness of the digital tool we wish to use, just as we would evaluate our own pedagogy depending on our context and subject specialism. We must on the one hand prepare our students for the digital future that they will encounter (Iivari et al., 2020), whilst at the same time upskilling our own digital literacies. In some situations, a Kahoot quiz makes an excellent replacement for mini whiteboards, whereas in other situations the use of self-marking MS Forms set as assignments in MS Teams is appropriate. The tools shouldn’t be used just because they are available. Rather, they should be used to enhance the learning process. If they don’t bring anything useful to the party, then what’s the point?

Teachers in the 21st century need a high level of digital competence. Indeed, there is an expectation from government that teachers will have at least a level one standard of digital literacy with the teaching of this embedded within their initial teacher training (Department for Education, 2023). Furthermore, without a high level of digital competence then the opportunities and enhanced learning outcomes that digital technology offer cannot be achieved.

Fortunately, there are a number of frameworks that can be deployed to help the teacher frame and improve their digital literacy skills, integrating digital technology with teaching. These are: the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEu), UNESCO ICT Competency Framework (ICT CFT), Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) and the SAMR Framework for Technology Integration (Bećirović, 2023).

TPACK is a framework that allows teachers think about the challenges in applying digital technologies in their teaching (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). As it focuses on the intersection of technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge (Koehler et al., 2013) it is my preference as a framework in which to consider the effectiveness of digital tools within my teaching. TPACK’s strong focus on integrating technology with technological knowledge is appropriate in teaching electrical apprentices due to the nature of electrical apprenticeship and the availability of digital tools. It allows for the complex nature of my discipline and acknowledges the “interweaving of many kinds of specialist knowledge” (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). The focus on problem solving, group work, and digital integration is especially useful as it matches my subject specific pedagogy. TPACK offers a way of measuring my progress and effectiveness of digitally transforming the curriculum and, as Koehler et al. (2013) point out, “move beyond oversimplified approaches that treat technology as an ‘add on’”.

Another consideration when integrating digital technology within teaching practice is the availability and quality of the IT and the availability of IT support. As we have seen with the Hole in the Wall project without sufficient IT support and resources the project fails or gets abandoned. Likewise, within our own settings we need IT systems that work if we are going to deeply embed digital learning. For example, it is quite common that IT support and infrastructure are behind the curve of digital pedagogical development and that networks within schools and colleges are not stable or fast enough to support the widespread digitisation of the curriculum. Or it might be simply the case that the mobile laptop trolley is never plugged in to charge overnight. IT support need to work together with practitioners allowing the experimentation with new digital tools rather than frustrate them with endless bureaucratic systems that make the implementation of new tools difficult or impossible. Decision makers and managers need to ensure that IT departments work with practitioners in enabling the development of digital tools based on good digital pedagogy enabling our students to have high class, quality digital education.

All of the above may well be true but the whole world is about to change and as Dickinson (2023) points out, AI is the “avalanche that is about to hit us”. It is going to be built into everything and as AI detectors do not work (Weber-Wulff et al., 2023) we need to rethink our pedagogy and assessment strategies (Lambert & Stevens, 2023) to take account of this. The old world is over now that ChatGPT4 can analyse your own writing and generate text in your style. Digital pedagogy needs to embrace an appropriate use of AI along with all the other digital tools. I find it equally exciting and scary so I’m leaving the last words to Douglas Adams: “Don’t Panic”.

References:

Adams, D, (1979). The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Pan Books

Adams, D (2002). The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time. Macmillan

Barrows, H. S. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 1996 (68), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219966804.

Bećirović, S. (2023). Fostering Digital Competence in Teachers: A Review of Existing Frameworks. In: Digital Pedagogy. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0444-0_5

Bruner, J.S. (1960). The Process of Education. Harvard University Press

City & Guilds (2018). City & Guilds Level 3 NVQ Diplomas in Electrotechnical Technology (2357) Qualification handbook. City & Guilds.

Department for Education. (2023) Overview: the initial teacher education system for FE. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/further-education-initial-teacher-education/overview-the-initial-teacher-education-system-for-fe

Dickinson, J. (2023, March 17). An avalanche really is coming this time. WonkHE. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/an-avalanche-really-is-coming-this-time/

Dunn, T. J., & Kennedy, M. (2019). Technology Enhanced Learning in higher education; motivations, engagement and academic achievement. Computers & Education 137. 104-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.004

Education and Teaching Foundation (2022). Professional Standards. Retrieved 21st October, 2023, from https://www.et-foundation.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/PS-for-Teachers_Summary-of-Standards_A4-Poster_Final.pdf

Gilster, P. (1997). Digital Literacy. Wiley Computer Pub.

Gravett, K., Baughan, P., Rao, N. et al. Spaces and Places for Connection in the Postdigital University. Postdigit Sci Educ 5, 694–715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00317-0

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable operations and Computers, 3, 275 – 285 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004

Hmelo-Silver, C., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2007). Scaffolding and achievement in problem-based and inquiry learning: A response to Kirschner, Sweller, and. Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701263368

Hughes, G., Upsher, R., Nobili, A., Kirkman, A., Wilson, C., Bowers-Brown, T., Foster, J., Bradley, S., & Byrom, N. (2022). Education for mental health: Enhancing student mental health through curriculum and pedagogy. Advance HE. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/advance-he/AdvHE_Education%20for%20mental%20health_online_1644243779.pdf

Iivari N, Sharma S, Ventä-Olkkonen L (2020) Digital transformation of everyday life–how COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? Int J Inf Manag 55:102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1). https://citejournal.org/volume-9/issue-1-09/general/what-is-technological-pedagogicalcontent-knowledge

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education, 193(3), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741319300303

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E.T., Fokkens-Bruinsma M., & de Boer, H. (2020) The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: a meta-analytic review, Research Papers in Education, 35:6, 641-680, DOI: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Lambert, J., & Stevens, M. (2023) ChatGPT and Generative AI Technology: A Mixed Bag of Concerns and New Opportunities, Computers in the Schools, DOI: 10.1080/07380569.2023.2256710

Mitra, S., & Rana, V. (2001). Children and the Internet: Experiments with minimally invasive education in India. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32 (2), 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00192

Piaget, J. (1964). Cognitive Development in Children: Development and Learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2, 176-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660020306

Polizzi, G. (2020). Digital literacy and the national curriculum for England: Learning from how the experts engage with and evaluate online content. Computers & Education 152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103859

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. MCB University Press, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Seely-Brown, J. (2008), “Foreword”, in Iiyoshi, T. and Kumar, M. (Eds), Opening up Education, MIT Press https://mitp-content-server.mit.edu/books/content/sectbyfn/books_pres_0/7641/7641.pdf?dl=1

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 2, 3-10. http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Stommel, J. (2018). Learning is not a mechanism. In An Urgency of teachers. https://pressbooks.pub/criticaldigitalpedagogy/chapter/learning-is-not-a-mechanism/

Warschauer, M (2003). Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6699.001.0001

Weber-Wulff, D., Ampjoma-Naumeca, A., Bjolobaba, S., Foltynek, T., Guerrero-Dib, J., Poppla, O., Sigut, P., & Waddington, L. (2023). Testing of Detection Tools for AI-Generated Text. Arxiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.15666.pdf